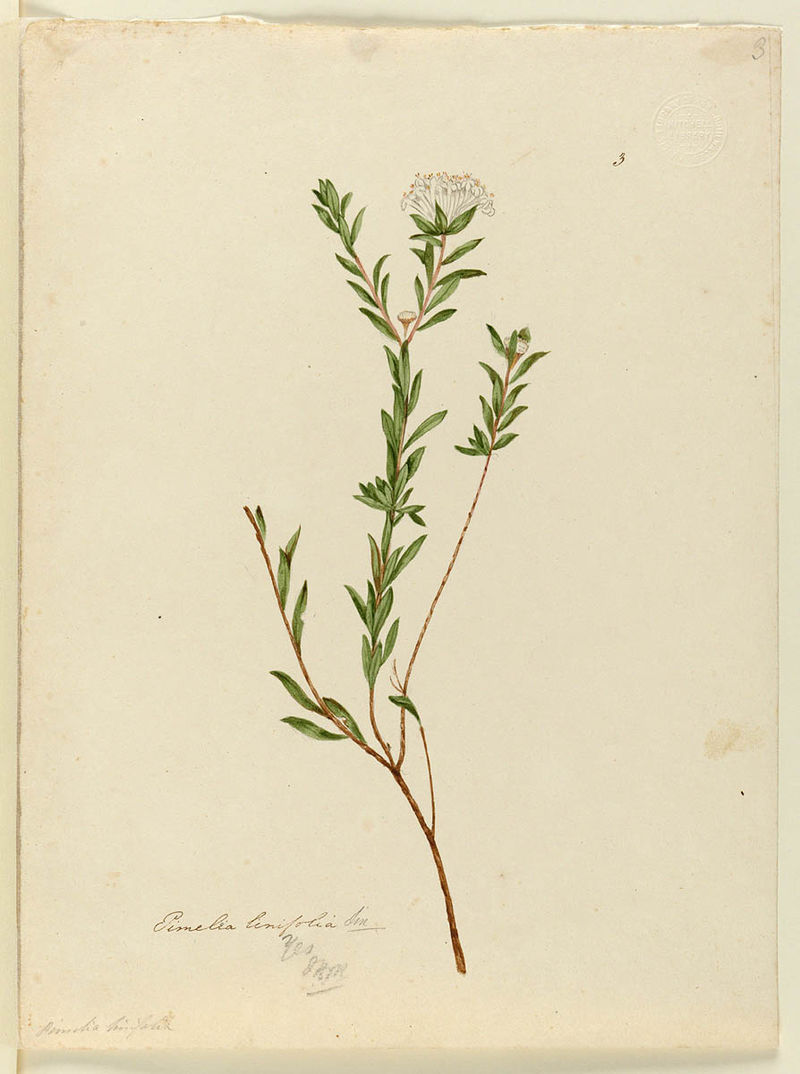

Pimelea linifolia

I loved White’s The Tree of Man and am surprised it took me so long to get around to reading Voss, especially since it’s a kind of neo-Victorian novel about a naturalist with delusions of grandeur and the angry, abrasive woman who loves him—and I’m all over that kind of thing. White reproduces the Victorian novelists’ style, character study, and themes with a gift for description that is dizzying, the way that spending too much time with a micro- or telescope can be dizzying: the perspective is off; one sees too much too close; we see veins pulsing and receding under the skin while people think, and smell the ants moving in the dirt, and come to experience soiled gloves and dying mules and cloud shadows as expressions of will. Through the huge cast of of characters, whose skins—not just their minds—White sets out to inhabit, he asks good questions: how does a god become a man, when the people around him believe him to be a man trying to become godlike? Is apotheosis a solitary or communal effort? What is humiliation? How does a 20th-century novelist find ways to collapse boundaries between individual and community when he confines himself to writing in a Victorian style about Victorian characters? And, given those self-imposed constraints, how does he speak about class, gender, race, and religion? Wondrous stuff.

Read April 2009